Story #1 Walter Loebenberg

In late September, as summer began its languid shift into autumn, Walter joined us in an archival vault of The Florida Holocaust Museum. A fraction of The FHM’s collection of art not currently on exhibit is stored there, held by tall, metal slats. As Walter sat down to share his personal story, these stored pieces stood behind him, stretching to the ceiling and lit in fluorescent detail, as if joining the conversation.

Before speaking, Walter clasped his hands together in his lap, flexed his broad shoulders. He is ninety-two years of age and holds himself with a rough softness. We turned on the camera, ran through some questions, and began to listen.

“We lived in a very small town,” Walter began. “Wächtersbach.”

(Walter at age 5 or 6 in Wächtersbach, Germany)

(Walter at age 5 or 6 in Wächtersbach, Germany)

Before the war, Wächtersbach — nestled in a valley between the Spessart and Vogelsberg mountain ranges of central Germany — was home to a vibrant Jewish community that dated back to the seventeen century. In the 1930s, as the country’s climate began to shift, it became difficult to live and function in the small town as a Jewish family. In school, often faced with attacks, Walter was subject to the rising tides of antisemitism. He was taught that the only way to survive was to strategize.

In 1936, the Loebenberg family moved to Frankfurt. Walter attended school and studied to become a Bar Mitzvah. It wasn’t long, though, before the nation’s rising antisemitism reached Frankfurt. On November 10, 1938, Kristallnacht, the “night of broken glass,” swept through the city.

Otto Tolischus of The New York Times wrote: “Beginning systematically in the early morning hours in almost every town and city in the country, the wrecking, looting and burning continued all day. Huge, but mostly silent, crowds looked on and the police confined themselves to regulating traffic and making wholesale arrests of Jews ‘for their own protection.’”

(Photo taken during Kristallnacht)

(Photo taken during Kristallnacht)

At the time, Walter was apprenticed at a bakery. He arrived for the morning shift and found it burnt to the ground, along with storefronts and businesses scattered across Gremany. His synagogue, too, was demolished. Photographs from the event show glass, freckling the streets; public assaults; books in heaps of fire. Later in the day, the police gathered the men from Frankfurt’s Jewish families — thousands of people — together in a large hall. On this day, the first train would leave from Frankfurt for a concentration camp. An official approached Walter and asked him for his age.

“Fourteen,” Walter said.

“When you hear these people move, go to the end of the hall, and I’ll meet you there,” the official said.

Walter walked to the end of the hall, and there he met ten other teenage boys. They were tasked with sweeping the floor as the rest of the Jewish men were evacuated. When the hall was emptied, they swept until the floor was clean. Police officers surrounded the group and ordered them to march from the hall. The youths were marched into the street and past a jeering crowd.

“Mostly women,” Walter said. “They wanted to kill us.”

When they reached the street, the police officers jumped aside.

“We were all young,” Walter said, “and we could run, so I ran home, hours and hours through the night.”

Soon after, Walter’s family booked passage on the MS St. Louis, a ship destined for Havana. But Walter’s mother was afraid if they went directly to Cuba she would never see her daughter again. So, she changed her mind at the last minute and re-booked the Loebenberg family’s passage on the SS Manhattan, an American ship that would pause for a layover in New York and then go on to Cuba. They visited Walter’s sister Helena on their journey to Cuba, but were not allowed to disembark because their visas were fraudulent.

“When we got to Havana,” Walter said, “they refused our visas. So we had to go back to New York on a ship.”

In May, Walter and his family began their trip to America on the SS Manhattan. The MS St. Louis and the SS Manhattan shared a night in Havana before the Manhattan set off for New York and the St. Louis was sent back to Europe. Walter remembers watching a man jump from the rim of the MS St. Louis and into the Atlantic Ocean. Only 278 of the 937 aboard the St. Louis survived the Holocaust.

In the summer of 1939, Walter and his family were detained on Ellis Island for four months. They were three people in a population of twenty-eight. Each day, the group was allowed two walks: one hour in the morning and one hour in the evening. In September, shortly after the United States entered into World War II, the detainees of Ellis Island were allowed to enter the United States legally though categorized as Hostile Aliens.

“They couldn’t do anything with us any more,” Walter said.

They were released into the United States, and the Loebenberg family moved to Chicago.

Walter enrolled in high school and grew up in the Midwest, where he quickly learned English as a second language. Upon graduating, he was drafted into the U.S. Army, which sent him to basic training in Wyoming, and which granted him U.S. citizenship.

While overseas, Walter was awarded with The Bronze Star Medal, presented to him by General Dwight D. Eisenhower, for his involvement with an interrogation that led to the information that saved the life of many American soldiers. After he returned to America, he met his wife Edith and they were married.

“I was married to Edie for 62 years. She was a wonderful person and I loved her very much,” Walter said.

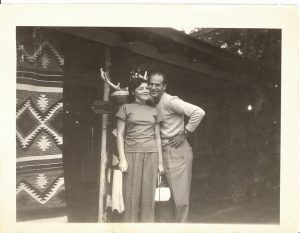

(Walter and Edie in the summer of 1947)

(Walter and Edie in the summer of 1947)

(Walter and Edie at a Museum event in 2006)

(Walter and Edie at a Museum event in 2006)

Several years ago, Walter returned to Wächtersbach. Many of the institutions that created a home for the Jewish community before the war have been covered over, converted, or repurposed. His family’s onetime synagogue is now a bank. The doorway still houses the name of the congregation, though, written in Hebrew text.

While the later years of the war are fading for Walter, his identity, he says, is shaped as much by his experience as an adult in the United States as it was shaped by his youth in Germany, his narrow escape.

“I am grateful for the opportunities that the United States gave me. I always knew that if I were able, I’d want to give back,” Walter said.

(Walter, Nobel Prize winner Elie Wiesel, Edie, and Amy S. Epstein opening The Florida Holocaust Museum in 1998)

(Walter, Nobel Prize winner Elie Wiesel, Edie, and Amy S. Epstein opening The Florida Holocaust Museum in 1998)

Walter Loebenberg cofounded The Florida Holocaust Museum with his wife, Edie, in 1992, with the support of community leaders. Walter acquired an original boxcar from Poland of the type used to transport over one hundred people at a time to concentration camps. The museum grew from there, drawing 24,000 visitors with its opening exhibit on Anne Frank, and became engaged in local and national efforts to educate youth and the public about the Holocaust. The voices of survivors have always been valued and essential parts of these educational efforts.

Story written by: Sarah Roth

Edited by: Kristen Wright