Story #13 Sabine Van Dam

(Childhood photo of Sabine. Photo credit: Holocaust Museum & Education Center)

(Childhood photo of Sabine. Photo credit: Holocaust Museum & Education Center)

Although the occupation radically transformed the lives of her parents, Sabine was too young to understand what was happening. Her parents and sister had to wear the Star of David when out in public, but her parents made sure that she was well fed and that her childhood was disrupted as little as possible for as long as possible.

But eventually things got worse. The Jewish people were slowly stripped of their rights and deprived of basic goods and services, such as public transit and use of the telephone. Sabine recalls this being tough for her parents. However, they carried on as best they could.

In 1942, a German decree ordered all of the Jews in Holland to move into the Amsterdam ghettos. This was a turning point for Sabine’s father: “He said we are not doing that, because we would be like a whole lot of sheep where they could do anything to us. That is when my father decided to flee.”

Some families, including that of Sabine’s late husband, were able to go into hiding. But that wasn’t easy, Sabine explained. “You had to know someone who was willing to risk. If a non-Jew was caught hiding Jews they faced the same fate as the Jews that they were hiding.” Sabine reflected on this risk: “Later in life I even asked myself, Would I have taken that risk for someone else? Would I have risked my children or save another child? In hindsight it’s easy, but I have never been able to answer this question.”

Because Sabine’s family had only lived in the Netherlands for a brief time, they did not know anyone who would be willing to hide them. Their only option was to try to flee. She remembers their escape. It was “a bright Sunday in May 1942. My mother came to my room and started to dress me and put on a sweater, a jacket, and another jacket.” They could not take suitcases, so as to avoid being conspicuous. Since they weren’t allowed to take public transit, their only option was to walk. As they walked down the street she recalls her family looking like the “Michelin Man,” encased in layers of clothing. She doesn’t know exactly how far they walked, but it felt like they “walked forever.” To this day she says, “I hate walking.”

Her father’s ambitious plan was to walk from the Netherlands to Belgium to France, and finally to Switzerland, which was not occupied. They walked until they reached the Dutch-Belgian border, where they had to sneak under the barbed wire fence because they didn’t have papers. They walked until they arrived in Antwerp, Belgium, where they found refuge in an abandoned house.

While in Antwerp, Sabine, her sister, and her mother did not leave the house. On a typical day, she recalls that her father would go out for around three hours. But one day, she recalls, “he was not back after three, four, four and a half hours. My mother was frantic, because here she was in a strange country, with two little girls, no phone, and we didn’t know anybody and were trapped in the house.”

She explained to us that during the time of the occupation, monetary rewards were offered for every Jew turned over to the authorities. A man had followed her father home and threatened to turn him in. Sabine’s father bargained with him, telling him that he could pay him more than amount of the reward. When her father finally arrived home, they paid off the man with her mother’s gold jewelry. Nonetheless, he threatened to turn them in the next day. It was time to flee again. “We waited a few hours,” Sabine said, “and put on all our clothes and started walking to Brussels, where we went to another house.”

Sabine is not sure, but she thinks her father must have been aided by the underground resistance. In Brussels, they lived with nine other people who were also fleeing the Nazi regime. Although they weren’t able to leave the house, she nonetheless has pleasant memories of this time. “I think this was the best part of the war. Everyone was willing to play with me. It was nice,” she said. The home in Brussels was the last place that her family lived together in freedom.

She will never forget their last day in that house, Sabine told us. She woke up to her door opening and thought that her father was bringing her a glass of water. When she called his name, she opened her eyes, and to her horror she saw a German soldier pointing a gun at her. “The whole house was freaked out,” Sabine recalls. Someone had given them away. They were forced into a van and taken to a prison.

After six weeks in the prison, the family was moved to the Mechelen (or Malines) transit camp, about twenty-five kilometers from Brussels. Between August 1942 and July 1944, more than 25,000 Jews along with several trainloads of Roma were sent from Mechelen to Auschwitz. Sabine’s parents were among these, although she and her sister were kept in Belgium.

Sabine would later learn that as Auschwitz was evacuated by the Nazis, her father was sent to the Mauthausen concentration camp and her mother to Bergen-Belsen, both camps located in Germany. Neither of them survived the camps.

“I am here because I missed the train, there were no more trains,” Sabine said.

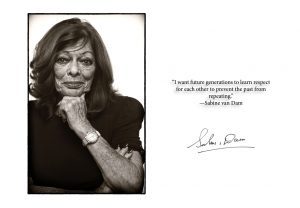

(Sabine in 2017. Photo credit: Erik Kellar Photography)

(Sabine in 2017. Photo credit: Erik Kellar Photography)

Sabine associates the day of the liberation with something unusual: the smell of French fries. “One day in September of 1944, the whole camp smelled of French fries,” she recalled. The Belgians “wanted to do something nice for us so they sent loads and loads of French fries.” Since that was the first thing she remembers from the liberation, French fries still have the profound “connotation of freedom” to her. Sabine and her eight grandchildren agree that, to this day, she still makes the best French fries.

After the war, Sabine and her sister were sent to an orphanage, which she describes as “miserable.” As other children were reunited with their families, they remained in custody in the orphanage. “In the camp,” she recalled, “you shared your misery. But in the orphanage, most people were better off than we were.”

They lived in the orphanage for a year and a half, until their uncle, their mother’s youngest brother, learned his nieces were alive and managed to send them a postcard. He eventually came and brought them back to The Hague to live and go to school.

Sabine describes life after the war: “I had normal life afterwards. Yes, I was married 55 years. My husband passed away. I have two children and eight grandchildren. I worked, we had a business. Normal life.” She and her husband owned an international textile company together. She describes herself now as a far-away snow bird: she still maintains residence in the Netherlands, but winters in Naples, Florida.

(Sabine and her late husband Jacques. Photo credit: Holocaust Museum & Education Center)

(Sabine and her late husband Jacques. Photo credit: Holocaust Museum & Education Center)

When she is in the United States she maintains an active involvement with the Holocaust Museum of South Florida. Sabine chooses to share her story, she said, “to remind us. To never forget. To try to teach a little good out of this horrible thing. But certainly, to remember. Six million Jews and the five million others, the homosexuals, the Jehovah’s witnesses and the handicapped.” She hopes to educate today’s youth to be more tolerant and respectful to one another.

She also maintains that people who see injustice must “take a side . . . . Because if less people had turned their backs, this would not have been such a big tragedy.”

A special thank you to The Holocaust Museum and Education Center of Southwest Florida for connecting us with Sabine Van Dam.

Story by: Timothy Walsh and Abigail Near-Oriola

Edited by: Sarah Hagerty, Jared Stark, and Kristen Wright