Story #3 Jacqueline Albin

When Jackie was two years old, her father was drafted into the French army where he served from 1939-1942. Therefore, it fell upon her grandparents and mother to provide a safe haven for the family after the German invasion of France in 1940. Jackie and her mother lived with her grandparents in Gex, a town in France near the Switzerland border, that had become part of the occupied zone. Living across the street from the German headquarters, Jackie remembers watching through the window of the house as guards patrolled the street.

(Jackie with her mother, father, and grandmother in 1938)

(Jackie with her mother, father, and grandmother in 1938)

In an effort to rejoin her husband in 1942, Jackie’s mother enlisted the help of a Christian friend to hike through the nearby mountainous region until they reached a place where she could safely remove the Star of David that Jews were required to wear. From there, she would board a train to meet her husband. Unaware of the dangers ahead, Jackie’s grandparents felt it was unnecessary for Jackie to leave. “They didn’t realize what was going on,” Jackie recalls.

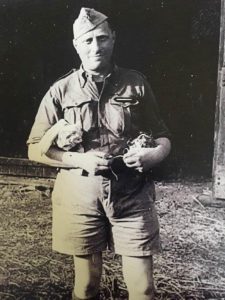

(Jackie’s father as a member of the underground.)

(Jackie’s father as a member of the underground.)

But Jackie’s mother insisted that her daughter join her. A few weeks after her mother left, the same Christian friend who had helped her mother came for Jackie. As they traveled together, he pretended to be her father, thus hiding her Jewish identity. “He was a very brave man,” Jackie recalls, “a wonderful man because he was not just putting himself at risk, but he was really putting his whole family at risk.” Shortly afterwards, her grandparents, who had stayed in the town, were picked up by French police collaborating with the Germans and eventually sent to Auschwitz where they were gassed on their arrival.

Once Jackie rejoined her parents, they lived together in a factory town where her father was able to find work. The general manager of the factory was not supposed to hire Jews. However, again at great peril to himself, he hired refugees and Jews in order to try to save, or at least help, some families. “When I talk to children,” Jackie notes, “I always emphasize that the reason I’m here is because there were people that helped us.”

(Jackie at the time of the reunion with her parents in 1942.)

(Jackie at the time of the reunion with her parents in 1942.)

In 1944, when the Germans were losing the war, Jackie, her mother, her newly born sister, and a group of others fled to the mountains because it was becoming more and more dangerous for them. Her father, who had joined the French Resistance, stayed behind to fight. But as the French Resistance began fighting more openly, it was no longer safe for their wives and children to remain.

Jackie recalls that once up in the mountains, her group was stopped by German soldiers. Thanks to some girls who, as Jackie put it, “had made friends with the soldiers,” Jackie’s group was able to return to their hometown hitching a ride with German soldiers who were retreating westward as they were losing the war. “I remember very vividly sitting on top of duffel bags, and my sister in the [baby] carriage, and my mother, going through all these little villages, with people looking at us, like, what are these people doing on top of these trucks?”

After reaching their town, Jackie and her family were shot at by a machine gun while waiting for a trolley car. But thankfully they were unharmed. “We were lucky,” she observes. “All four of us—my nuclear family, my mother, my father, my sister, and I—came through the war okay.”

After the war ended, Jackie’s mother was able to reunite with her mother and brothers–German Jews who managed to leave Germany in time and who were already living in Chicago. Because she could not speak any English, Jackie, although already ten years old, was placed into first grade. “If you could view yourself when you were ten, and put together with kids six years old, you will understand that it was very traumatic for me,” she recalls. Thanks to one of the teachers at the school, however, Jackie was able to move from the first to the sixth grade in just a few months. Because she dressed and spoke differently, however, she was the object of rude comments from her classmates. “It wasn’t physical bullying or anything like that,” she remembers, “but it really hurt.” When she speaks to groups of children at The Florida Holocaust Museum, she shares her experience as an ostracized refugee to teach lessons of tolerance and empathy towards others.

(Jackie conducting a docent-led tour at The FHM in 2015)

(Jackie conducting a docent-led tour at The FHM in 2015)

After years of living with this past, Jackie and her mother visited The Florida Holocaust Museum one day. Jackie remembers that the Museum was seeking volunteers, and her mother said that it might be something she would enjoy. Believing that “Survivors” meant those who were in concentration camps, Jackie didn’t realize that she would eventually come to teach visitors about her own personal past. “And then, when I was taking the docent class,” she recalls, “I realized I was a Survivor.” Only after several years of serving as a docent did she begin to share her own story.

Jackie has since donated her father’s French Resistance uniform armband, hat, and some additional artifacts to The Florida Holocaust Museum and feels that the Museum is important in that it keeps the victims’ stories alive. To her, it is crucial to remember not only the Holocaust but also other genocides in the world. When she looks at the world today, she told us, “I’m sad, I guess—that’s one word, though it’s really not the right word—about what’s going on in the world and the fact that we say, ‘never again,’ but it happens over and over again.” She now expresses deep gratitude towards The Florida Holocaust Museum for emphasizing the continued relevance of Holocaust history and memory.

“I think the goal is that we help to make the world a better place, and that’s what it needs to be,” said Jackie.

(Jackie sharing her Holocaust Survivor story with over 300 students and 30 teachers (via Skype) at Santa Fe Catholic High School in Lakeland, FL in 2016.)

(Jackie sharing her Holocaust Survivor story with over 300 students and 30 teachers (via Skype) at Santa Fe Catholic High School in Lakeland, FL in 2016.)

Story by: Karolina Perez, Emily Freeman, and Megan Weiss

Edited by: Jared Stark and Kristen Wright