Story #5 Jerry Rawicki

Jerry Rawicki was born in 1927 in the historic town of Płock, Poland, located sixty miles west of Warsaw along the Vistula River. Jews had lived in Płock since the 13th century, making it one of the oldest Jewish communities in Poland. In the early 19th century, Jews comprised half the town’s population, and in 1939 made up approximately 25% of the town’s roughly 40,000 inhabitants. “We had a nice life,” Jerry says of the time before World War II. But after the German invasion of Poland, when he was twelve years old, his education was interrupted and “things were completely different than my normal life.” He would go on to survive confinement in ghettos, fighting in the heroic but doomed Warsaw Ghetto uprising, and over a year of perilous hiding on the Gentile side of Warsaw.

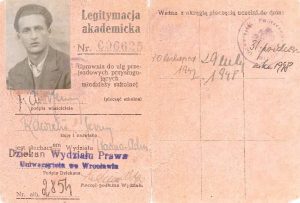

(Jerry around age 2 with his mother in Płock, Poland)

(Jerry around age 2 with his mother in Płock, Poland)

Immediately following the Nazi occupation of Poland in September 1939, Jerry recalls that “we of course did not know what was happening to us, to Jews in general.” He heard rumors and began to learn more about Hitler and his plans from whatever radio broadcasts and newspapers were accessible. Then came restrictions on Jews, such as curfews. “We had begun to realize that the life would never be as it used to be.”

At first the restrictions were minor, but they were implemented in ways intended to cause confusion. For instance, at noon a notice would be posted announcing a five o’clock curfew, but later, in another street, a three o’clock curfew would be posted, leading to arrests and beatings. Punishments were initially minimal, but then the deportations began. “We were told to take all our belongings that we could carry with us, all the necessities….. Whatever else, what we’re leaving, we were told, was going to be sent to us. Because deception, by Germans, was used, all the time, alongside brute force.”

Jerry’s deportation occurred on a freezing day in January. He waited in the cold for the flat-bed trucks that would take them to a transit camp in Northern Poland. Because there was no room on the trucks for the belongings they had packed, they were told, “leave it, we will send it to you.” Again, Jerry said, they were deceived.

Upon arriving at the transit camp, barren barracks with locked restrooms and nothing but straw on the floors for sleeping served as an introduction of what was to come. After three days in the transit camp, Jerry was loaded onto a train with five hundred other Jews and sent south to a small village where about one hundred Jews had lived before the war. “They had little store fronts,” he recalls, “but they were told by the Germans to vacate those stores, and that was our housing.”

The conditions in this small ghetto were cramped and unhygienic. “You can imagine, five hundred people descending—or dumped, so to speak—on a small community like this, where there were a few empty storefronts. And that was our home.” There, Jerry lived in a room with three families, fourteen people in total. Conditions were horrible. There was only one water spigot with dirty water, no place to wash, and no soap. Lice spread quickly and there was no medication, which led to people becoming ill with typhus. “We were being decimated by the disease,” Jerry remembers.

It was the hunger that remains with him most of all. “It was something that almost turned us into animals. We couldn’t think of anything, we couldn’t do anything, we couldn’t function normally, all we want to do is get a piece of bread. So people were dying from hunger, too.”

Jerry shared with us an image of what he called “daily life for Jews in the Holocaust.”

“We could see people that we knew for all our lives—of course at that time I was about thirteen or fourteen years old—people that I’ve known, people that I’ve looked up to, elderly people, neighbors. You could see somebody you knew all your life, and that you looked up to … and you see a person lying in the street, you could hardly remember, hardly recognize the person, because things were oozing from his nose, and face, mouth, and he was dying, or, dead.”

During the time in the ghetto, there was no access to radio, newspapers, or any news other that rumors and gossip. Nonetheless, news started to trickle in that at the end of the trains were gas chambers and crematoria. He also heard about larger cities like Warsaw that were forming resistance movements in the larger ghettos.

With his oldest sister, Jerry escaped to Warsaw in 1942 and joined his father in the Warsaw Ghetto, where he joined the Jewish Fighting Organization as a courier.

“It wasn’t easy to transport any guns, ammunition, anything worthwhile that the resistance could have,” he reported. “But nevertheless, the resistance procured enough bullets and revolvers, and of course we were making what they call Molotov cocktails, which were just bottles filled with gasoline.”

Jerry describes the uprising as very short. The Germans had more power than the Jewish Underground. Before they knew it, the ghetto was burning. Those who survived managed to hide in cellars or whatever they could find.

After he had run out of ammunition, Jerry hid in an abandoned cellar. Sick and tired from weeks of fighting, he was captured by German satellite troops and taken to Umschlagplatz in Warsaw, where the last surviving Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto were being sent to the death camps. But in a moment of confusion, he managed to escape the Umschlagplatz and was eventually able to contact his sister, who was living on the Gentile side of Warsaw with false papers. She was able to get some food to him, and he managed to hide in attics, cellars, and wherever else he could find a safe place.

One day, Jerry decided to take a walk outdoors. It was around June, not a very hot day, and he met and talked with some non-Jewish young boys around his age. It was still wartime, but it was the first time in a long time Jerry experienced “normal life.” Two of the boys left to go home, but, Jerry recalled, “one of them stayed with me, and we talked for another couple of hours or so maybe, and finally he says to me, let’s go home. And I realized that the jig was up [because] I didn’t have a home.”

Although it was extremely risky, Jerry admitted to the boy that he was a Jew. His new friend did something shocking; he invited Jerry back to his home and allowed him to stay the night in the family’s shed, giving him a pillow and blanket. Jerry stayed there for a few weeks, then left Warsaw for the countryside, where he managed to pose as a farm boy. This is how he survived until the end of the war.

After the war, Jerry returned to Poland to complete his education, and completed one year of university, studying law. But in order to continue his education in communist Poland he would have had to give up his passport. Instead, Jerry left Poland, staying first in Sweden for a year then coming to the United States in 1948. Because he did not know English, he could not continue to study law and instead went to trade school to become an optician. He eventually moved to Pittsburgh, where he married and had two children.

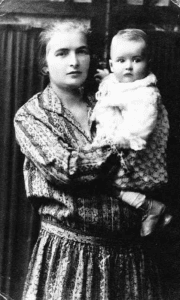

(Jerry in 2008. Photo credit: Bob Croslin, Tampa Bay Times)

(Jerry in 2008. Photo credit: Bob Croslin, Tampa Bay Times)

When he moved to Florida, Jerry became involved with The Florida Holocaust Museum. For Jerry, the 25th anniversary of The Florida Holocaust Museum honors all the good work the Museum has done regarding the education of the Holocaust.

“It is not easy to tell people about the Holocaust,” he said. “But the education, exhibits, and different events the Museum sponsors makes it easier to reach schools, the community, and young people. This is all so very important, and such a noble, noble effort, to make sure that the Holocaust would not be forgotten.”

Jerry is a frequent guest speaker at The Florida Holocaust Museum. He continues to share his story with young people, school groups, and visitors to the museum.

(Jerry speaking to students and visitors at The Florida Holocaust Museum in 2017)

(Jerry speaking to students and visitors at The Florida Holocaust Museum in 2017)

This week he celebrates his 90th birthday.

Story by: Sarah Hagerty and Jamie Kleckowski

Edited by: Jared Stark and Kristen Wright