Story #9

Holocaust Survivor: René Hammond

Location: Pinellas Park, FL

In honor of the 25th Anniversary of The Florida Holocaust Museum (The FHM), this oral history series shares the stories of twenty-five Holocaust Survivors. Each Survivor brings to the series an individual voice that enlivens our understanding of the Holocaust; the war’s effects on individuals, families, and communities dispersed across the world; and its reverberations into the present moment.

René Hammond (née Koenigsberg) was born in 1925 in Uzhhorod. She was 91 years old when she shared her testimony with us at her home in Pinellas Park.

Once part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and today part of Ukraine, René’s native town of Uzhhorod had been annexed to the Republic of Czechoslovakia after World War I, and became part of Hungary after the First Vienna Award in 1938. Jews had been an important presence in Uzhhorod since at least the 16th century. Around the time of René’s birth, Uzhhorod’s approximately 7,500 Jews made up more than a quarter of the total population of approximately 26,000. By 1941, the Jewish population would number 9,576, of whom only a few hundred would survive the war.

Growing up in Czech Uzhhorod, René recalls her childhood as a normal one. “If you compare it to teenagers in the United States, pretty much the same,” she told us.

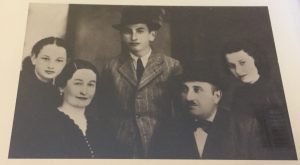

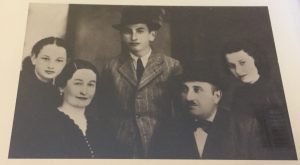

(Photo of René’s family taken in 1939 or 1940 in Hungary)

(Photo of René’s family taken in 1939 or 1940 in Hungary)

But once Hungary gained control of the city in 1938, things changed. She and her Jewish classmates were expelled from Hungarian schools and had to attend a Hebrew academy. This turned out to have its advantages, because there she studied English for three years, which turned out to be immensely useful after the war. But when Germany occupied Hungary in March 1944, her education was interrupted, just before she was scheduled to graduate from high school. The Jews of Uzhhorod were forced to wear the yellow star and interned in ghettos.

“When the Germans came in, we had to start wearing a yellow star on our clothes,” she recalled. “We had a curfew, we weren’t allowed to be out of the house after a certain time, I don’t remember what the time was. And then came the order that we are going to be taken to a farm to work. We could take with us whatever we could carry. That happened either March or April, I am not positive of the date. They came into our house with guns and pushed us out of our houses into a wire place, like a ghetto, where we stayed.”

Several weeks later, in mid-May 1944, René and her family were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

“In Auschwitz,” René told us, “they separated us, first the men from the women, then what they considered the older people from the younger people. My mother was only 46 years old. She was separated into the group of older people and very young children, well, babies, toddlers, and probably up to 16 years or so, anybody that couldn’t work. They put older people and the children on a truck, telling us that being they can’t walk that far to take a shower—that’s why they are going in a truck. The other ones that were younger, we could walk to the shower.”

René described to us in detail the process of being registered in the camp as a prisoner. “We had to undress, they shaved our heads, they cut our—shaved our hair, and they told us to put all our possessions and just our clothes and whatever we brought with us, and that after the shower we’ll get it back. Well, that was another lie. We never got anything back. After the shower, they gave us a grey prisoner’s dress with a number on the sleeve. And then from there they took us into the barracks where they had …tiers? I can’t remember what they call them, but it was two, one on the bottom and one on top, and each one had six people, which means that we couldn’t lie down, we could just sit all the time. Then they gave us a piece of bread that looked like . . . we didn’t know what it was when we got it. It looked like brick. It was hard. And then we found out it was bread and we should eat it. On the way to the showers we could see older people lying on the road in the ditches that were dead—they were either shot or they just died from exhaustion. When we asked when we’ll see our parents, they said, you won’t see your parents, they are dead.”

Only later did she realize what had happened to her parents. “When we arrived in Auschwitz we saw a flame, we had no idea what it was, but it was a big flame. It turned out it was from the crematorium from where they burned people.”

After approximately six weeks in Auschwitz, René was sent to work in German factories, first to a satellite of the Buchenwald concentration camp at Gelsenkirchen, Germany. When that camp was burned down in Allied bombing raids, she was sent to the Buchenwald satellite camp at Essen.

“We suffered a lot, guards that we had, they were SS and they were very cruel. For any little thing they would hit you. And one of them told us once that no matter who wins the war, they would always have enough time to kill us,” René said about her time in Essen.

While at Essen, she traveled to work at the Krupp factory every day. There, she met a German man who told her and her friends that he would help them if they were able to escape, because the war would be ending soon. While deciding if they would try to escape or not, René recalled thinking, “If we escape we have a chance—maybe we can survive by hiding. If they take us back to Auschwitz—it only means one thing, death.”

René and her friends knew that the guards hid during Allied bombing raids, and so they took this as an opportunity to escape. “To us it was like fireworks,” René described the bombings at Essen. “We said, well it’s tonight or never.”

They hid in a cellar, and after a few days they found the German man who promised to help them. René, her sister, and two other girls were taken in by a few different people until the war was over. René later discovered that her brother had also survived the war.

(René with her sister Agnes, and Elisabeth and Erna Roth/Anolik in 1945)

(René with her sister Agnes, and Elisabeth and Erna Roth/Anolik in 1945)

René recalled seeing the American army. “When the troops were marching in, taking over the city, we were out there waving at them and welcoming them. Of course, the German people looked at us that we were traitors. They didn’t realize that they were [the traitors]—that it meant freedom for us.”

After the war, René went to work for the British military government and married an American serviceman in Germany. She moved with him to the United States in 1948 and together they had five children.

When speaking about the twenty-fifth anniversary of The Florida Holocaust Museum she says, “It means that there is hope, there is always hope, and you should never give up. And I hope that it never happens again, even though you were questioning antisemitism, there is a lot of it, especially now in Europe, some of the countries, but hopefully it won’t get as far as it did in Germany. And also, the fact that we have Israel. There is somebody who would be speaking up for us wherever we are. It means a lot.”

She believes The Florida Holocaust Museum is vital because it educates people to prevent genocides from happening again. “Well I think it’s a good thing that it’s there, that people can go and people can find out about it and they are taught what can happen if . . . well, that it never happens again and that people learn about it. It’s history.”

Story by: Jennifer Mohn, Jamie Kleckowski, and Emily Freeman

Edited by: Jared Stark and Kristen Wright

(Photo of René’s family taken in 1939 or 1940 in Hungary)

(Photo of René’s family taken in 1939 or 1940 in Hungary) (René with her sister Agnes, and Elisabeth and Erna Roth/Anolik in 1945)

(René with her sister Agnes, and Elisabeth and Erna Roth/Anolik in 1945)