Story #17 Rob Nossen

By the time Rob was seven, his immediate family—his parents, his older brother, and himself—would survive two internments in the Westerbork transit camp in Holland as well as deportation to the Theresienstadt ghetto near Prague. Of the fifteen members of Rob’s family who had sought refuge in Amsterdam, only Rob and his immediate family survived the war.

Rob’s family life in Amsterdam was comfortable at first. “Everything was fine, until 1940,” he recalled. “Most Dutch did not believe that Germany was going to invade, the reason being that in the First World War, Holland was neutral. It’s a small country, and in many ways, the Germans and the Dutch are very similar, the same background, the same ethnicity . . . . So nobody expected Holland to be invaded.”

In 1940, Germany invaded Holland. “Holland fell in a matter of five days,” Rob explained. Rather than send troops, the Nazis bombed strategic areas, such as Rotterdam, a major port. “That was a new warfare, it wasn’t expected.” His family tried to reach the ocean to get to England, where one of Rob’s aunts lived, but the road was blocked. “We went back home and just sat it out,” Rob told us.

“Unlike in other countries, in Eastern Europe, the Germans never really set up the ghettos” in Amsterdam, Rob said. However, in 1941, the first restrictions were put in place, similar to the Nuremberg Laws in Germany. Jews were not allowed in public parks, swimming pools, or restaurants. They were also restricted from driving cars and leaving the city limits. “We could still function, but it became more and more difficult.”

In 1942, further constraints were implemented. Many Jews were also forced to move to Amsterdam to enable further roundups. “There was a sense that they knew where the Jews were. We had to register as well. So there was no place to go,” Rob said.

At that time, many Jews went into hiding. “But it was very difficult, if you were a German Jew, to hide, because you didn’t speak Dutch, or if you did speak Dutch it was with an accent, a German accent,” Rob said. Most German Jews also lacked the friends and contacts that Dutch citizens had, which were necessary to hide effectively. “We were kind of exposed.”

After being forced out of Dutch schools, the Jewish community opened its own schools. In 1942, Rob’s brother attended the same school as Anne Frank for a few months, before she went into hiding.

Around the same time, deportations started in Amsterdam. “The timing coincided with formation of the gas chambers, and a lot of the German Jews were rounded up,” Rob told us. Included in these early deportations was one of Rob’s cousins by marriage, a German nun of Jewish background who had fled to Holland in 1938. Sister Teresa Benedicta of the Cross (born Edith Stein) was beatified by Pope John Paul II in 1987, and canonized twelve years later.

Later that year, Rob’s grandmother died, and his family had to obtain a special permit to bury her outside the city limits. In January of 1943, Rob’s grandfather was deported. “We don’t know what happened to him,” Rob said. “So we assume, because there’s no record of him—the Germans were meticulous in maintaining records—that he went to the gas chamber immediately, which was not unusual.”

By the summer of 1943, ghettos throughout Europe had been liquidated. This coincided with much larger deportations throughout Nazi-occupied countries. “In June of 1943, they had the first major round-ups. And it wasn’t just in Holland, it was in Belgium, Denmark, all of the Western countries that were occupied, France and so forth, so June and July were major round-ups,” Rob told us.

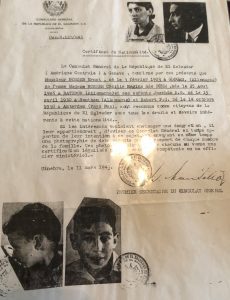

Rob’s family was taken to Westerbork, a transit camp in Holland where most Jews were taken before being deported farther east. Unusually, they were held in Westerbork for close to three months, then allowed to return to Amsterdam. Rob cites two reasons for his family’s atypical treatment. First, in March, 1943, Rob’s father obtained papers from the El Salvadoran consulate in Geneva granting his family El Salvadoran citizenship. Second, the company his father worked for also helped return Rob’s family to Amsterdam by claiming that it required his father’s special skills in metallurgy and chemical engineering. “So in September we were allowed back to Amsterdam. That didn’t happen very often,” Rob said. “But we had lost everything.”

(Rob Nossen’s family papers from the El Salvadoran consulate in Geneva granting his family El Salvadoran citizenship)

(Rob Nossen’s family papers from the El Salvadoran consulate in Geneva granting his family El Salvadoran citizenship)

In 1944, conditions changed once again for the Jewish people. “What changed then,” Rob explained, “was the D-Day landings. The Allies came into Western Europe, and they liberated France, they went up to Belgium, liberated Belgium, and got to the southern part of Holland.” With the Allies approaching, Germany deported the last Jews remaining in Holland, except for those in mixed marriages or other special circumstances.

Rob’s family was sent back to Westerbork, just one year after being allowed to leave, and from there were deported to Theresienstadt, a “model ghetto” and concentration camp in German-occupied Czechoslovakia. In Theresienstadt, Rob lived with his mother, because he was only six years old, while his brother and father lived in a different section of the barracks. Eventually, Rob’s family got a room in an officer’s quarters, where five different families each had their own rooms but shared kitchen and bathroom facilities. “We were lucky,” Rob recalled, to be able to live together as a family.

Living in Theresienstadt’s ghetto, rather than its concentration camp, they were able to wear civilian clothes and work regular jobs. Rob’s mother was an administrator at the hospital, and his father worked in a laboratory. “The ghettos were set up so that the Jewish community ran the ghetto,” Rob said, although the Nazis controlled the rations and other aspects of life in Theresienstadt. “But within the ghetto we had schools, we had a hospital, things like that.”

In the summer of 1944, Germany used Theresienstadt to show representatives of the International and Danish Red Cross how Jews were being treated. Rob recalled how the Germans laid out walkways, set up dining halls, and even a field for children to play soccer, in order to create the impression that Jews were living comfortably. The Germans limited who the Red Cross representatives were allowed to talk to, in an attempt to preserve the illusion. “By 1944 the world knew about the gas chambers, they knew about the death camps,” Rob explained. “It was a farce, the whole thing was a farce.” As soon as the Red Cross left, the deportations increased.

By the last months of 1944, the Nazis began destroying evidence of their crimes. “The Nazis knew the Russians were coming. So they cut it down, they dismantled the gas chambers, the crematoriums, so that they wouldn’t find them.” At Theresienstadt, ashes were thrown into the river to hide how many had been killed.

In April of 1945, thousands of prisoners on death marches from other camps arrived in Theresienstadt. Many had diseases and were kept in quarantine. Rob shared a story where a head of cabbage had somehow gotten across the fence from the quarantine area, and Rob tossed it back over to the quarantined side. When he told his parents about the cabbage, they were upset. “Typhus was rampant in the camps at that point, and they didn’t know whether it was diseased.”

In May 1945, Theresienstadt was abandoned by the Nazis and taken over by the Czech Red Cross until the Russian army arrived.

Rob believes there were many things that kept his family alive. His mother sewed money into clothes, to bribe the Germans for extra food and other necessities. In the hospital, where Rob’s mother worked, it was common to hide deaths from the Germans, in order to keep extra rations. Rob’s father was also able to smuggle supplies from the laboratory.

While his brother contracted tuberculosis and spent a long time in the hospital, Rob stayed relatively healthy. “I was in the children’s home, because both my parents were working, so I ended up getting extra rations,” Rob recalls. The residents of the ghetto controlled the children’s home, so they made sure that the children got extra food. Rob was often fed a kind of fatty pork, which he never liked, but it helped him maintain his health.

After being transferred to an American DP camp following the liberation of Theresienstadt, Rob’s family moved back to Amsterdam in June of 1945, where his father returned to work and his brother went back to school. Rob, at age seven, started grammar school. However, conditions in Holland were still less than ideal.

By 1948, Rob’s brother had finished high school in Amsterdam, so his parents considered it a good time to leave. His father also feared that there was nothing to stop Russia from invading Western Europe. “Every country that was liberated by the Russians, they left their troops there,” Rob explained.

With no family left in Europe, Rob’s family moved to the United States, to Patterson, New Jersey, where they joined an aunt who had left Germany in 1937.

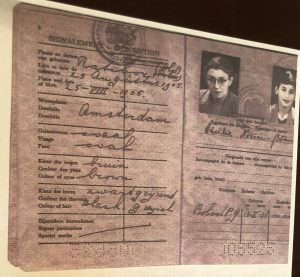

Rob was able to travel on his mother’s passport due to his young age, but legally he was considered stateless. He was born in Holland, but because his parents were German immigrants, he was not considered a citizen of either country.

(Rob’s mother’s passport)

(Rob’s mother’s passport)

While his parents and brother spoke English, Rob knew only German and Dutch. But after starting school, Rob learned English quickly. “There was no English as a second language or special programs for me,” Rob recalled. “They just put me in a classroom. Fortunately I had good teachers . . . . By January or so I was fluent.”

After high school Rob attended Columbia University, which was one of the few schools at the time to have a Navy ROTC program. Upon graduating in 1960, Rob enlisted in the U.S. Navy and was on active duty for four and a half years, then spent another twenty years in active reserve. During this time, he met Fran, whom he married in 1963.

(Rob speaking with students at the Holocaust Museum and Education Center of Southwest Florida)

(Rob speaking with students at the Holocaust Museum and Education Center of Southwest Florida)

Rob retired in 1994 and moved to Naples, Florida, where he still lives today. Rob is heavily involved with the Holocaust Museum and Education Center of Southwest Florida in Naples, where he often shares his story with school groups. Rob is committed to educating future generations about the Holocaust, as well as teaching messages of tolerance. “It’s kind of scary in some ways,” Rob told us, “because I see a lot of stuff happening today in the world, throughout the world—we’re moving backwards.” However, to Rob, this reaffirms the importance of museums and education centers and of telling his own story.

Story by: Leah Hart and Lever Stewart

Edited by: Sarah Hagerty, Jared Stark, and Kristen Wright