Story #14 Renée Fritz

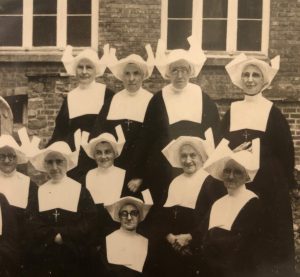

(Renée with her mother in Vienna, 1937)

(Renée with her mother in Vienna, 1937)

Renée later learned her family history from her mother. Her parents had been well-known retailers and were able to establish black market connections after the war began. When Renée’s father was taken to Dachau early in the war, her mother was able to obtain a false passport for him through the black market and was able to help get him released from the camp. Renée’s mother told him, “Just get passage to anywhere you can, just as long as you get out of Europe, and then, you know, we’ll follow.” Her father left for America, but Renée’s mother could not have predicted that the war would escalate the way it did, preventing Renée or her mother from joining her father in America.

Renée’s mother eventually joined her in Belgium, where they went into hiding in the basement of a factory with her whole family, including her parents’ siblings. After hiding in the factory for some time, by chance Renée’s mother struck up a conversation with a well-intentioned Catholic woman, Mrs. Degelas. “For some reason, the woman seemed to sense that something wasn’t right,” Renée says, and the woman asked her mother if she was Jewish. When Renée’s mother said yes, Mrs. Degelas offered to take in Renée’s family and hide them in her three-story townhome. “I would be more than happy to put all of you up,” she said.

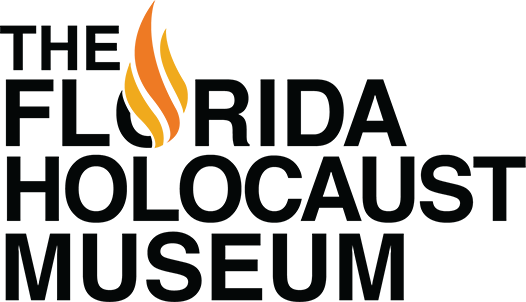

(Renée in Vienna 1939, age 2)

(Renée in Vienna 1939, age 2)

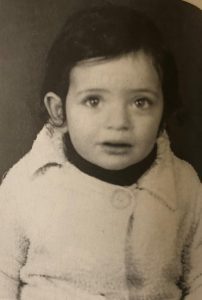

Renée’s mother accepted the offer, but because Renée was so young at the time, still only three years old, the adults were concerned that she would not be able to remain quiet and keep everyone safely hidden. Mrs. Degelas was closely involved in her church, where she asked her pastor to help find a place where Renée could be hidden in safety. Once again, Renée left her family, this time for a convent in Belgium where she assumed a false name and was raised as a Catholic.

Renée learned to find comfort in the routine of her new life: “I knew the rosary and all these, you know, different saints and days, and the Mother Superior gave me a large pin and said that every time that I knew a prayer for that certain saint’s day that I would get a new medal.” Renée was able to stay in the convent for a few years, until the Nazis became suspicious that the convent was working with the underground resistance. The nuns were able to find a family living on a farm in the country who were willing to take Renée in.

(Some of the nuns who helped keep Renée safely hidden)

(Some of the nuns who helped keep Renée safely hidden)

On the farm, Renée enjoyed playing with one of the children, a girl close in age, as well as learning about the farm animals. However, the family’s neighbors eventually grew suspicious. “If you turned anybody in for hiding any Jews, you know, they got paid by the Nazis,” Renée recalls.

One night, a man showed up to take Renée to a Protestant orphanage. Renée was almost ten years old by this time and had grown accustomed to life in hiding. “I had no life beforehand,” Renée says, “so I didn’t know what a mother was or father was. I was used to it . . . . Well, as used to it as you can get.”

Renée now lived as a Protestant among numerous other children at the orphanage. She would remain in the orphanage until the end of the war. It was located across the street from the main Nazi headquarters in the area and was close to where the Battle of the Bulge was fought. When Germany lost the Battle of the Bulge in January 1945, American forces took control of the Nazi headquarters across from the orphanage. “They would come with their jeeps and they would give us all kinds of, you know, little candies and so forth and so on,” Renée says. An American soldier from New Orleans, Jack Schultz, grew close to Renée and decided he wanted to adopt her.

(Renée at the orphanage across from Nazi headquarters before the end of the war, 1944)

(Renée at the orphanage across from Nazi headquarters before the end of the war, 1944)

In order for Jack to adopt Renée, he needed to contact the Red Cross. The Red Cross discovered that Renée’s mother had survived Auschwitz, after being deported along with her entire family. Renée’s mother was the only survivor from her family. Renée later found out that her mother had initially been placed in the same line as the rest of her family, to be sent to the gas chambers, but was recognized by a Nazi soldier she had gone to school with. The soldier told her to step into the other line, and Renée’s mother survived by working in an ammunition factory in Auschwitz for the remainder of the war.

(Left: Renée and Jack Schultz in 1945 and Right: Renée and Jack in 1967)

(Left: Renée and Jack Schultz in 1945 and Right: Renée and Jack in 1967)

When asked how she was able to survive Auschwitz, Renée’s mother replied, “I did not want to leave my child as an orphan.” Because her mother’s health had become so poor, it was a couple years before she was strong enough to come to the orphanage and collect Renée. When her mother finally arrived, Renée remembers: “I didn’t know what a mother was. I was very disappointed because I really wanted to go with Jack. You know, he was the first person that showed me any form of attention.”

For a while, Renée and her mother stayed in a one-bedroom apartment in Brussels, until they were able to leave for America. Renée had two uncles who had left Europe before the war, one of whom served in the United States Army. They were able to help Renée and her mother move to America.

Renée was thirteen when she arrived in America and had never attended school, nor could she speak any English—though she spoke four other languages: German, French, Flemish, and Yiddish. Renée and her mother were soon reunited with Renée’s father, who had originally taken a ship to America but was denied entry and sought refuge in Canada. A distant cousin was able to sponsor his emigration to America, and the family was reunited.

Renée struggled to adjust to life with her family. “It was very difficult, because first of all, I wasn’t used to a male figure at all. I was used to being pretty independent and running around wherever I wanted to, and doing things, you know, on my own more or less. Really I just lived with them for six years of my life—7th and 8th grade and my four years of high school.” Renée recalls that her mother was like a stranger to her, because they had been separated when Renée was so young. “I never knew what the mother figure was all about,” Renée says.

Renée had a hard time in school and found English difficult to learn but says that she had a lot of “chutzpah” and eventually received a bachelor’s degree in education from Boston University, after marching down to her high school principal’s office and asking him to make a phone call to get her into the university.

At Boston University, Renée met a friend from high school, Joyce, who helped Renée with her studies. “Poor Joyce should have gotten two degrees because she had to explain everything,” Renée recalls, “I couldn’t type. She had to type my papers. I mean she really . . . she was like a private coach for me for four years of college. She really was.”

When she was younger, Renée rarely shared her story. “I never spoke about it at home,” Renée recalls, “because my feeling was that I was so young . . . and nothing really happened to me. Unless I was a camp survivor, why even speak about any of these things? Because I was too young, you know, to understand.”

Despite being too young to fully understand the war while it was happening, Renée understands its impact: “I found out afterwards, you know, years later, that because the children had no bonding with anyone really, we never bonded, you know, and it tormented us, you know, in our more adult lives.”

Renée’s mother was also hesitant to share her own story. “She wouldn’t talk about it to me. She spoke about it to my husband but not to me. She never talked about it to me, because she figured, you know, I’d been through my own thing, why burden me?”

As Renée looks to the future and reflects on the past, she wants to share her story. “I feel that this generation, especially in the States, are growing up, they don’t realize the trauma that this can create. That any kind of war can create on people. . . . I firmly believe that it can happen here. Just as well as anywhere else. I think that it’s very important that they learn the lesson. It’s not just happening to someone else. It can happen to you.”

(Renée in Bloomfield, Connecticut, 1989)

(Renée in Bloomfield, Connecticut, 1989)

Renée began to tell her story to school groups while she was still living in Connecticut and became involved with the Holocaust Museum of Southwest Florida in Naples upon moving to Florida. “The minute I moved down here I started getting involved with the museum,” Renée says, “I get involved also by going to schools and having people come to the museum and, you know, walking around telling them a part of my story. Just to educate them. Because, you know, I feel that after my generation, that’s it. I mean, you’re never going to have a live witness again. We’re the last of it. We really are. So you know everything will be second-hand then, you’ll have to read it in a book. And I think it’s more realistic when it’s one-to-one, when you’re speaking to a person who has lived that trauma. And it is trauma. That’s all I can tell you.”

A special thank you to The Holocaust Museum and Education Center of Southwest Florida for connecting us with Renée Fritz.

Story by: Abigail Near-Oriola and Timothy Walsh

Edited by: Sarah Hagerty, Jared Stark, and Kristen Wright